Health

Health

Child mortality

Author/s: Nadine Nannan (Burden of Disease Research Unit, MRC) and Katharine Hall

Date: October 2025

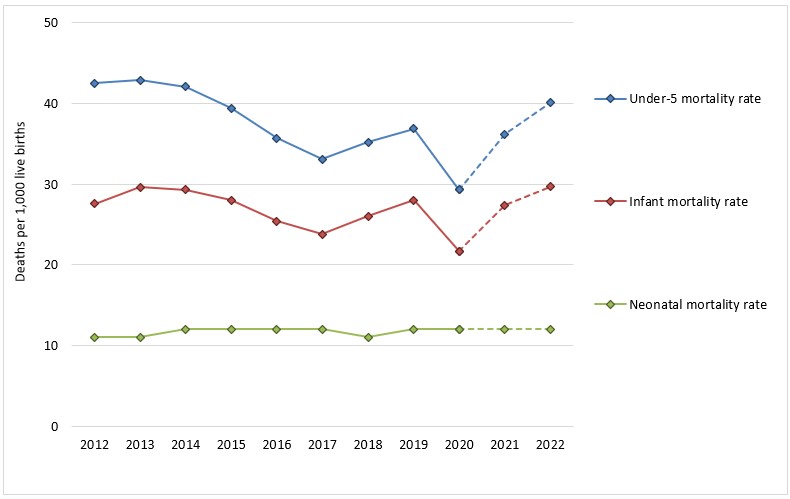

The infant mortality rate (IMR) is defined as the probability of dying within the first year of life, and refers to the number of babies under 12 months who die in a year, per 1,000 live births during the same year. Similarly, the under-five mortality rate (U5MR) is defined as the probability of a child dying between birth and the fifth birthday. The U5MR refers to the number of children under five years old who die in a year, per 1,000 live births in the same year. The neonatal mortality rate (NMR) is the probability of dying within the first 28 days of life, per 1,000 live births.

2015-2019 mortality rates from Dorrington RE, Bradshaw D, Laubscher R & Nannan, N (2021) Rapid Mortality Surveillance Report 2019-2020. Cape Town: South African Medical Research Council.

2012-2014 and 2021-2022 mortality rates derived from the same Medical Research Council Rapid Mortality Surveillance project published by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation and available at https://childmortality.org/all-cause-mortality/data?refArea=ZAF&indicator=MRY0T4. Note that the 2021 and 2022 RMS estimates are preliminary and have not yet been published by the MRC.

The infant and under-five mortality rates are key indicators of heath and development. They are associated with a broad range of bio-demographic, health and environmental factors which are not only important determinants of child health but are also informative about the health status of the broader population.

Ideally this information is obtained from vital registration systems. However, as in many middle- and lower-income countries, the under-reporting of births and deaths renders the South African system inadequate for monitoring directly. South Africa is therefore reliant on alternative methods, such as survey and census data, and modelling (particularly given the lateness in release of registration data), to determine the extent of the deficiency in the registered deaths. Unfortunately, the most recent survey data that can be used date back to 2016/7 and the most recent data on deaths released by Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) is four years out of date.[i]

An alternative approach to monitoring age-specific mortality nationally since 2009 is the rapid mortality surveillance system (RMS) based on the deaths recorded on the population register by the Department of Home Affairs.[2]

These data have been corrected for known biases. In other words, the trends shown in Figure xx are based on nationally representative numbers. The RMS reports vital registration data adjusted for under-reporting which allows for the evaluation of annual trends.

Trends since 2000 show that the IMR peaked in 2003 at 54 per 1,000 and decreased to 24 per 1,000 in 2017, after which the IMR rose again slightly before a sudden drop to 20 in 2020. During the same period the U5MR decreased from 81 per 1,000 in 2003 to 33 per 1,000 in 2017, rising again slightly to 36 in 2019 and then dropping to 28 in 2020.[3]

With reference to the substantial drop in infant and under-five mortality in 2020, the authors of the Rapid Mortality Surveillance Report note that “the lack of seasonal increases in the numbers of registered deaths suggest that the winter increases in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and other pneumonias as well as seasonal outbreaks of diarrhoea were absent in 2020.”[3]

This was possibly due to the effects of lockdown with “unusually low” monthly deaths in April and May 2020, and “no seasonal trend in the following [winter] months”.[3]

In other words, while the hard lockdown of 2020 was devastating for the economy and society in many ways, an unexpected benefit was that the restrictions on socialising and travel may have protected young children from infectious diseases that contribute to high mortality rates.

Preliminary estimates by the MRC suggest that infant mortality rates rose sharply in 2021 and 2022, with a corresponding increase in under-five mortality. The revised estimate for IMR in 2022 is 29 deaths per 1,000 live births. Despite slight recovery (to 26 in 2023) the estimated probability of dying in the first year of life remains above pre-COVID levels. The U5MR increased to 39 in 2022, declining slightly to 35 in 2023 – also above pre-COVID rates.

The reasons for rising child mortality after lockdown are unclear as there have been long delays in the release of Causes of Death data by Stats SA. Mortality estimates beyond 2019 are extrapolations from the National Population Register (NPR), which is more prone to error because not all deaths are reported, and even if they are, they are not captured in the NPR if the birth was not registered prior to death. The NPR also does not record births and deaths for individuals who are not South African. In addition, there is quite a bit of uncertainty around the population estimates for children, and for infants in particular. This is partly due to problems with the high undercount of the 2022 census and subsequent adjustments to correct for that. In addition, administrative data on births, recorded in the Department of Health’s District Health Information System (DHIS), shows an inexplicable decline to 2016 and rise to 2020 followed by an improbable decline the number of live births from 2021 onwards, calling into question the integrity of the system.

It is partly due to these data delays, gaps and quality concerns that the MRC has not formally published its child mortality estimates since 2020, although the estimates have been shared with the United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN-IGME) and inform the UN models.

Given the lack of recent data on causes of death, it is not possible to determine what is driving the estimated increase in mortality between 2020 and 2023. The leading causes of under-five mortality (other than neonatal causes) are generally diarrhoea, pneumonia and other respiratory infections, while malnutrition is often an underlying cause of death in young children.

The neonatal mortality rate (NMR) is the probability of dying within the first 28 days of life per 1,000 live births. The NMR has remained stable, at around 12 deaths per 1,000 live births. Estimates of the NMR are taken from the UN-IGME model, which is in turn derived from neonatal deaths and live births recorded in the DHIS. The NMR estimates therefore exclude deaths that occur at home or in the many private sector health facilities that are not included in the DHIS. Unlike the live birth trend, the DHIS reflects no substantial change in neonatal deaths.

The DHIS also records the in-facility neonatal death rate – i.e. the number of infants aged 0 – 28 days who died during their stay in the facility, per 1,000 live births in public health facilities. The recorded rates were also around 12 in the years leading up to COVID-19 but increased after 2020, reaching 13.4 per 1,000 live births in 2023.[4]

Demographic and Health Surveys are considered a ‘gold standard’ for measuring child mortality in developing countries. The last reliable empirical estimates come from the 1998 DHS. The failure of the 2001 census and the 2003 DHS to collect the information necessary for the calculation of childhood mortality rates made subsequent estimates impossible to derive from the data. Data from the 2016 SADHS have over-estimated neonatal mortality.

The SAECR 2024 tracks trends on the status of children under 6.

The SAECR 2024 tracks trends on the status of children under 6.