Definition

This indicator shows the proportion of adolescents (aged 15 – 17 years) in a national prevalence survey who report having been hit, beaten or physically hurt in any way by an adult in their lifetime. This indicator does not capture incidents of physical bullying by peers.Data

Notes

Children are defined as persons aged 0 – 17 years.

Source

Artz L, Burton P, Ward C et al (2016) Optimus Study South Africa: Technical Report. Sexual Victimisation of Children in South Africa. Final Report of the Optimus Foundation Study: South Africa. Zurich: UBS Optimus Foundation (p84-85). Household weighted data, self-administered questionnaire.

What do the numbers tell us?

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child defines physical violence against children as including all corporal punishment and all other forms of torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment as well as physical bullying and hazing by adults or other children. In extreme cases, this form of violence can result in a child's death.

Those who intentionally use physical force against children are often adults in positions of trust and authority, such as a child's caregivers, family members or teachers. Children may also experience physical violence at the hands of their peers.

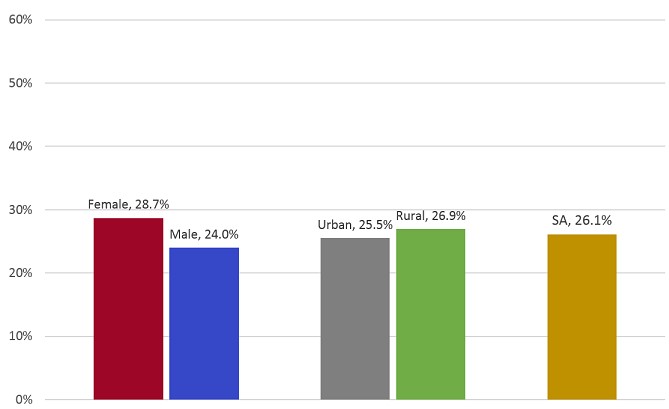

The 2016 Optimus study on the sexual victimisation of children in South Africa also included questions about other forms of victimisation such as physical abuse. Drawing on the self-administered component of the household survey, the Optimus study estimated that a quarter (26%) of adolescents had experienced physical abuse by an adult in their lifetime.1

While the estimates provided by the different data collection methods used in the 2016 Optimus study produced a wide range of estimates, the researchers noted that the rates reported in the study are "considerably higher" than the global average of 22.6% cited in a meta-analysis of rates of physical abuse around the world.2 Some community-based studies within the country have produced even higher estimates; for example, a community-based study in Mpumalanga and the Western Cape (which used a five item measure rather than relying on a single question as in the Optimus study) found that over half of children in these communities (56%) reported lifetime physical abuse.3 There was no significant difference between boys and girls, and the perpetrators were most commonly primary caregivers, followed by teachers and relatives.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Artz L, Burton P, Ward C et al (2016) Optimus Study South Africa: Technical Report. Sexual Victimisation of Children in South Africa. Final Report of the Optimus Foundation Study: South Africa. Zurich: UBS Optimus Foundation.

2 Stoltenborgh et al. (2013), cited in Artz et al (2016), p39.

3 Meinck F, Cluver L, Boyes M & Loening-Voysey H (2016) Physical, emotional and sexual adolescent abuse victimisation in South Africa: prevalence, incidence, perpetrators and locations. J Epidemiol Community Health, 70:910-916.

Those who intentionally use physical force against children are often adults in positions of trust and authority, such as a child's caregivers, family members or teachers. Children may also experience physical violence at the hands of their peers.

The 2016 Optimus study on the sexual victimisation of children in South Africa also included questions about other forms of victimisation such as physical abuse. Drawing on the self-administered component of the household survey, the Optimus study estimated that a quarter (26%) of adolescents had experienced physical abuse by an adult in their lifetime.1

While the estimates provided by the different data collection methods used in the 2016 Optimus study produced a wide range of estimates, the researchers noted that the rates reported in the study are "considerably higher" than the global average of 22.6% cited in a meta-analysis of rates of physical abuse around the world.2 Some community-based studies within the country have produced even higher estimates; for example, a community-based study in Mpumalanga and the Western Cape (which used a five item measure rather than relying on a single question as in the Optimus study) found that over half of children in these communities (56%) reported lifetime physical abuse.3 There was no significant difference between boys and girls, and the perpetrators were most commonly primary caregivers, followed by teachers and relatives.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Artz L, Burton P, Ward C et al (2016) Optimus Study South Africa: Technical Report. Sexual Victimisation of Children in South Africa. Final Report of the Optimus Foundation Study: South Africa. Zurich: UBS Optimus Foundation.

2 Stoltenborgh et al. (2013), cited in Artz et al (2016), p39.

3 Meinck F, Cluver L, Boyes M & Loening-Voysey H (2016) Physical, emotional and sexual adolescent abuse victimisation in South Africa: prevalence, incidence, perpetrators and locations. J Epidemiol Community Health, 70:910-916.

Technical notes

The 2017 Optimus study on child sexual victimisation was commissioned by the UBS Optimus Foundation and carried out by researchers from the Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention and the Department of Psychology and Gender Health and Justice Research Unit at the University of Cape Town.

The study consists of a population-based survey and an accompanying school-based survey, as well as a qualitative agency component. The household survey was based on a multi-stage stratified sample that was designed to produce a nationally representative sample and which used province, geographic area (urban/rural) and race group as explicit stratification variables (see p23 of the technical study report for more detail). A power allocation of 0.4 was used to increase the sample size in the smaller strata. The schools, on the other hand, were clustered according to the Enumerator Areas (EAs) identified in the household survey and so this data is not representative of the school population.

Between 5 and 10 interviews were conducted in each EA for the household study, and one adolescent aged 15 – 17 years was interviewed per selected household. Where a given household included more than one child in the required age group, one was randomly selected using either a Kish Grid or interviewing the young person whose birth date occurred the earliest in the year. Active informed consent was obtained from parents and informed assent was obtained from the adolescent. At the schools, a total of 30 interviews were completed; 10 learners each were randomly selected from grades 10 to 12. Passive parental consent was sought at schools, so that parents were requested to complete signed consent forms if they did not want their child to participate in the study.

The household sample consisted of 5 631 participants, while the school-based survey comprised 4 086 learners. The refusal rate for households was 5.2%, and 3.9% for learners at schools.

The study included both interviewer administered questionnaires and a self-administered component. In reporting the findings, we have drawn on the self-administered data where possible as we consider them to be more reliable given the anonymity involved. There does appear to have been a greater willingness to disclose in the self-administered component, with rates reported in this component generally being higher than rates reported in the interviewer-administered component.

The study consists of a population-based survey and an accompanying school-based survey, as well as a qualitative agency component. The household survey was based on a multi-stage stratified sample that was designed to produce a nationally representative sample and which used province, geographic area (urban/rural) and race group as explicit stratification variables (see p23 of the technical study report for more detail). A power allocation of 0.4 was used to increase the sample size in the smaller strata. The schools, on the other hand, were clustered according to the Enumerator Areas (EAs) identified in the household survey and so this data is not representative of the school population.

Between 5 and 10 interviews were conducted in each EA for the household study, and one adolescent aged 15 – 17 years was interviewed per selected household. Where a given household included more than one child in the required age group, one was randomly selected using either a Kish Grid or interviewing the young person whose birth date occurred the earliest in the year. Active informed consent was obtained from parents and informed assent was obtained from the adolescent. At the schools, a total of 30 interviews were completed; 10 learners each were randomly selected from grades 10 to 12. Passive parental consent was sought at schools, so that parents were requested to complete signed consent forms if they did not want their child to participate in the study.

The household sample consisted of 5 631 participants, while the school-based survey comprised 4 086 learners. The refusal rate for households was 5.2%, and 3.9% for learners at schools.

The study included both interviewer administered questionnaires and a self-administered component. In reporting the findings, we have drawn on the self-administered data where possible as we consider them to be more reliable given the anonymity involved. There does appear to have been a greater willingness to disclose in the self-administered component, with rates reported in this component generally being higher than rates reported in the interviewer-administered component.

Strengths and limitations of the data

A strength of the prevalence survey is that it captures incidents that are not reported to the authorities and therefore do not appear in administrative data. The Optimus survey drew on different sites (home and school) and different methods of collecting the data (interviewer and self-administered questionnaires), and provides a sense of how the approach taken can influence the levels of reporting.

A potential limitation was the ethical requirement of obtaining parental consent in the household survey. Consent and informed assent is essential to research ethics, but there is a concern that parents who may themselves be abusers may have refused to consent and therefore biased the results.

A further limitation is that the data cannot be disaggregated beyond provincial level, and in some cases the small numbers reporting various forms of abuse makes disaggregation of the weighted data even to this level difficult. Obtaining data at a lower level (e.g. district) is important for understanding where violence against children is most prevalent, and which groups of children are most at risk.

Lastly, this survey fills an important data gap in understanding the prevalence of sexual violence against children (in the context of other forms of violence), but it is not a regular survey and does not provide routine surveillance data that can be used to monitor trends over time.

A potential limitation was the ethical requirement of obtaining parental consent in the household survey. Consent and informed assent is essential to research ethics, but there is a concern that parents who may themselves be abusers may have refused to consent and therefore biased the results.

A further limitation is that the data cannot be disaggregated beyond provincial level, and in some cases the small numbers reporting various forms of abuse makes disaggregation of the weighted data even to this level difficult. Obtaining data at a lower level (e.g. district) is important for understanding where violence against children is most prevalent, and which groups of children are most at risk.

Lastly, this survey fills an important data gap in understanding the prevalence of sexual violence against children (in the context of other forms of violence), but it is not a regular survey and does not provide routine surveillance data that can be used to monitor trends over time.

The SAECR 2024 tracks trends on the status of children under 6.

The SAECR 2024 tracks trends on the status of children under 6.