Definition

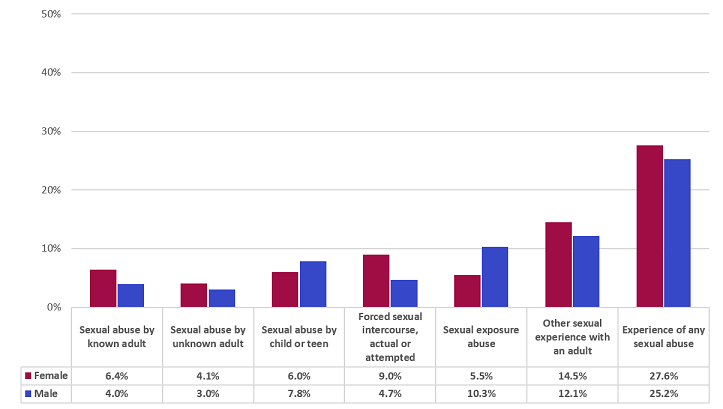

The 2016 national prevalence survey on child sexual victimisation was conducted with adolescents aged 15-17 years. To measure child sexual victimisation, researchers asked about various scenarios as shown below. Overall, 26% of adolescents reported experiencing at least one (or more) of these situations. Data

Notes

1. Participants in this study were adolescents aged 15 to 17 years old.

Source

Artz L, Burton P, Ward C et al (2016) Optimus Study South Africa: Technical Report. Sexual Victimisation of Children in South Africa. Final Report of the Optimus Foundation Study: South Africa. Zurich: UBS Optimus Foundation (p84-85). Household weighted data, self-administered questionnaire.

What do the numbers tell us?

The 2016 Optimus study was the first national prevalence survey on the sexual victimisation of children in South Africa. The different methods of data collection used in the study provided a range of estimates of the prevalence of sexual victimisation nationally: more than a quarter (26%) of adolescents aged 15 - 17 years in the household survey reported experiencing some form of sexual victimisation in their lifetime, while 35.4% of young people interviewed at schools reported some form of sexual abuse.

Previous community-based studies have tended to note gender differences in the prevalence of sexual victimisation. For example, a retrospective community-based survey in the Eastern Cape asked young adults about their experience of sexual violence before the age of 18 and found that 38% of young women and 17% of young men reported sexual abuse.1 A recent community-based study in Mpumalanga and the Western Cape also found that girls were more likely than boys to report sexual harassment, contact sexual abuse and rape.2 The 2016 Optimus study did not find marked differences in the overall reporting of sexual abuse amongst adolescents (as shown in the table above), but the researchers argue that "the findings from this national prevalence study indicate that boys and girls are equally vulnerable to some form of sexual abuse over the course of their lifetimes, although those forms of sexual abuse tend to be different for boys and girls, with girls more likely to experience 'contact sexual abuse' than boys, who report higher levels of 'exposure' and non-contact forms of sexual abuse".2 They also found that boys are particularly unlikely to confide in others or report incidents of sexual victimisation, and they argue for the inclusion of boys in both prevention and intervention.

Comparisons of prevalence rates of sexual abuse across contexts are notoriously difficult given the variations in definitions and measurement. A point to note about the broad definition adopted in the Optimus study is that it includes sexual experiences with someone aged 18 years or older in the definition of sexual abuse. However in some cases this may be consensual and where the age gap is minimal, it can be argued that such instances do not constitute victimisation.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Jama N, Puren A (2010) Associations between childhood adversity and depression, substance abuse and HIV and HSV2 incident infections in rural South African youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(11): 833-841.

Previous community-based studies have tended to note gender differences in the prevalence of sexual victimisation. For example, a retrospective community-based survey in the Eastern Cape asked young adults about their experience of sexual violence before the age of 18 and found that 38% of young women and 17% of young men reported sexual abuse.1 A recent community-based study in Mpumalanga and the Western Cape also found that girls were more likely than boys to report sexual harassment, contact sexual abuse and rape.2 The 2016 Optimus study did not find marked differences in the overall reporting of sexual abuse amongst adolescents (as shown in the table above), but the researchers argue that "the findings from this national prevalence study indicate that boys and girls are equally vulnerable to some form of sexual abuse over the course of their lifetimes, although those forms of sexual abuse tend to be different for boys and girls, with girls more likely to experience 'contact sexual abuse' than boys, who report higher levels of 'exposure' and non-contact forms of sexual abuse".2 They also found that boys are particularly unlikely to confide in others or report incidents of sexual victimisation, and they argue for the inclusion of boys in both prevention and intervention.

Comparisons of prevalence rates of sexual abuse across contexts are notoriously difficult given the variations in definitions and measurement. A point to note about the broad definition adopted in the Optimus study is that it includes sexual experiences with someone aged 18 years or older in the definition of sexual abuse. However in some cases this may be consensual and where the age gap is minimal, it can be argued that such instances do not constitute victimisation.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Jama N, Puren A (2010) Associations between childhood adversity and depression, substance abuse and HIV and HSV2 incident infections in rural South African youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(11): 833-841.

2 Meinck F, Cluver LD, Boyes ME & Loening-Voysey H (2016) Physical, emotional and sexual adolescent abuse victimisation in South Africa: prevalence, incidence, perpetrators and locations. J Epidemiol Community Health, 70:910-916.

Technical notes

The 2016 Optimus study on child sexual victimisation consisted of a population-based survey and an accompanying school-based survey. The household survey was based on a multi-stage stratified sampling strategy that was designed to produce a nationally representative sample and which used province, geographic area (urban/rural) and race group as explicit stratification variables. The schools, on the other hand, were clustered according to the Enumerator Areas identified in the household survey and therefore the schools data is not representative of the population.

One adolescent aged 15 – 17 years was interviewed per selected household. Active informed consent was obtained from parents and informed assent was obtained from the adolescent. A total of 30 interviews were completed within each school; 10 learners each were randomly selected from grades 10 to 12. Passive parental consent was sought at schools, so that parents were requested to complete signed consent forms if they did not want their child to participate in the study. The household sample consisted of 5 631 participants, while the school-based survey comprised 4 086 learners. The refusal rate for households was 5.2%, while the rates for schools were 3.9%.

The study included both interviewer administered questionnaires, and a self-administered component. In reporting the findings, we have drawn on the self-administered data as we consider this data to be more reliable given the anonymity involved. There does appear to have been a greater willingness to disclose in the self-administered component, since self-administered reporting was generally higher than reporting rates on the interviewer-administered questionnaires.

One adolescent aged 15 – 17 years was interviewed per selected household. Active informed consent was obtained from parents and informed assent was obtained from the adolescent. A total of 30 interviews were completed within each school; 10 learners each were randomly selected from grades 10 to 12. Passive parental consent was sought at schools, so that parents were requested to complete signed consent forms if they did not want their child to participate in the study. The household sample consisted of 5 631 participants, while the school-based survey comprised 4 086 learners. The refusal rate for households was 5.2%, while the rates for schools were 3.9%.

The study included both interviewer administered questionnaires, and a self-administered component. In reporting the findings, we have drawn on the self-administered data as we consider this data to be more reliable given the anonymity involved. There does appear to have been a greater willingness to disclose in the self-administered component, since self-administered reporting was generally higher than reporting rates on the interviewer-administered questionnaires.

Strengths and limitations of the data

A strength of the prevalence survey is that it captures incidents that are not reported to the authorities and therefore would not appear in administrative data. The Optimus survey also drew on different sites (home and school) and different methods of collecting the data (interviewer and self-administered questionnaires), and shows how the approach taken can influence the levels of reporting.

A potential limitation was the ethical requirement of obtaining parental consent in the household survey. Consent and informed assent is essential to research ethics, but there is a concern that abusive parents may have refused consent, thus biasing the results.

A further limitation is that the data cannot be disaggregated beyond provincial level, and in most cases the small numbers reporting various forms of abuse makes disaggregation even to this level difficult. Obtaining data at a lower level (e.g. district) is important for understanding where violence against children is most prevalent and which groups of children are most at risk.

Lastly, this survey fills an important data gap in understanding the prevalence of sexual violence against children (in the context of other forms of violence) but it is not conducted on a regular basis and therefore does not provide surveillance data needed to monitor trends over time.

A potential limitation was the ethical requirement of obtaining parental consent in the household survey. Consent and informed assent is essential to research ethics, but there is a concern that abusive parents may have refused consent, thus biasing the results.

A further limitation is that the data cannot be disaggregated beyond provincial level, and in most cases the small numbers reporting various forms of abuse makes disaggregation even to this level difficult. Obtaining data at a lower level (e.g. district) is important for understanding where violence against children is most prevalent and which groups of children are most at risk.

Lastly, this survey fills an important data gap in understanding the prevalence of sexual violence against children (in the context of other forms of violence) but it is not conducted on a regular basis and therefore does not provide surveillance data needed to monitor trends over time.

The SAECR 2024 tracks trends on the status of children under 6.

The SAECR 2024 tracks trends on the status of children under 6.